Researchers have developed a device enabling individuals with amputations to experience natural temperature sensations through their prosthetic limbs, adding a human touch to social interactions.

The new "MiniTouch" system uses off-the-shelf electronics, can be integrated into commercially available prostheses, and does not require surgery. The setup incorporates a temperature sensor that covers the prosthetic hand's index finger pad and a thermode that heats or cools in the socket that connects the prosthesis to the residual arm stump.

Phantom limb refers to the sensation of feeling and experiencing an amputated limb. Despite the absence of the physical limb, people often perceive its presence due to residual neural pathways in the brain. This phenomenon can include sensations like touch, motion, and even thermal perception.

"In some specific areas of the residual arm, when we apply a cold or hot stimulus, the sensation is perceived there, directly on the skin, but it's kind of projected, it's perceived as coming from the phantom hand, from the missing hand," said Jonathan Muheim, a doctoral student at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, Switzerland, and co-author of the study, in an interview with Tech Times. "These sensations are very realistic; it's like it's their biological arm."

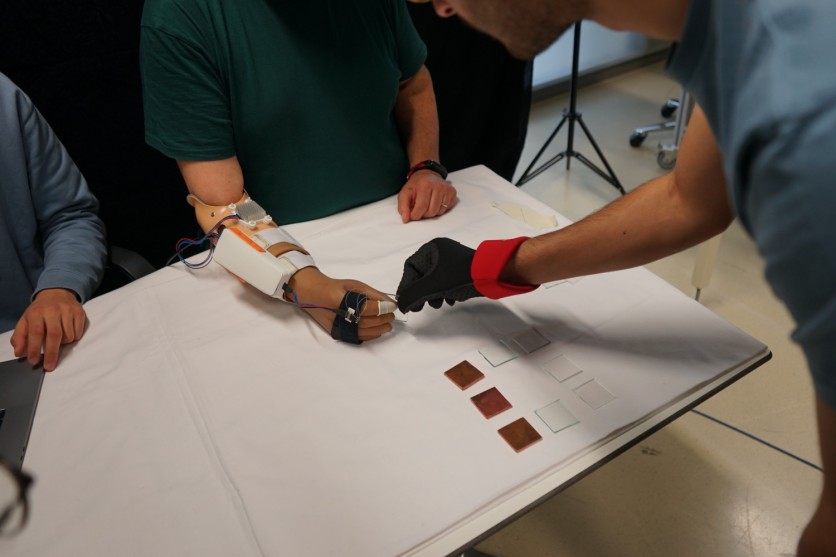

Muheim and his colleagues tested MiniTouch on a 57-year-old amputee to see if it could be a valuable tool for temperature perception. The system has two main components: a thin-film sensor and a thermal display. The thin sensor is placed on the fingertip of a prosthetic hand and collects thermal information that is then integrated and sent to the thermal display, which is in contact with the skin of the residual limb.

In the first test, the amputee was asked to use a thermal prosthetic hand to interact with bottles of cold, ambient, or hot water, all of which appeared identical. The participant accurately perceived the temperature in each case, achieving the same success rate as when using his intact hand. In addition, the researchers assessed the participant's sensitivity to subtle thermal nuances by having him explore copper, glass, and plastic surfaces while blindfolded. Using the thermal prosthetic hand, the participant distinguished between these materials 67% of the time, demonstrating comparable accuracy to his intact arm.

Further tests examined the amputee's ability to discriminate between a human arm and a prosthetic arm through tactile sensation. Again blindfolded, the participant was instructed to touch real and artificial arms, using a softer silicone hand for comparison. When MiniTouch was on, the participant correctly identified the type of arm he touched in 80% of trials. This result is significant because it shows that MiniTouch can help amputees feel people's temperatures, improving their ability to connect with loved ones.

"Temperature is connected with effective touch," explained Giacomo Valle, a researcher at the University of Chicago who wasn't involved in the study. "So, when you interact with another person, if you touch their hand, their body, and you feel their temperature, you can create more intimate connections," he adds.

In a final assessment, the researchers observed how the thermal device helped detect temperature changes while manipulating objects. The participant was asked to move cubes between boxes, where the cubes varied in temperature, and the boxes represented hot and cold zones. When the MiniTouch system was active, the participant consistently placed more than half of the blocks correctly across all sessions. Conversely, performance dropped when the system was deactivated.

The researchers behind the study say their technology is technically ready, but more safety testing is needed before it reaches clinics. They also want to explore how the system could be useful to people other than amputees.

"Now that we have this device, we're trying to see if it can help us understand thermal sensation more broadly in other populations as well," Muheim explains. "For example, in healthy people, and also in other clinical populations that have sensory problems, such as stroke patients."

Valle told Tech Times that he hopes the technology will reach patienst soon. "Thermal sensation is a part of the sensory experience that has been completely missing from available prosthetics," he says. "This is the first time we've seen this kind of thermal feedback in a prosthetic."

But Valle cautioned that the device may only work for some. "My only concern is that not all amputees have this residual sensation in the stump," he added. "Maybe this is a solution, but not everyone can really experience it."

Bárbara Pinho is a freelance science journalist. Her work work has appeared in New Scientist, Chemistry World, Discover, Chemistry & Industry News, National Geographic. Her website is https://www.barbarapinho.com/

ⓒ 2026 TECHTIMES.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.