In an earlier study, researchers at Georgetown found that repeated head impacts prompt adaptations in the brain's synaptic functioning. The frequency of these impacts may result in challenges related to memory recall and the formation of new memories.

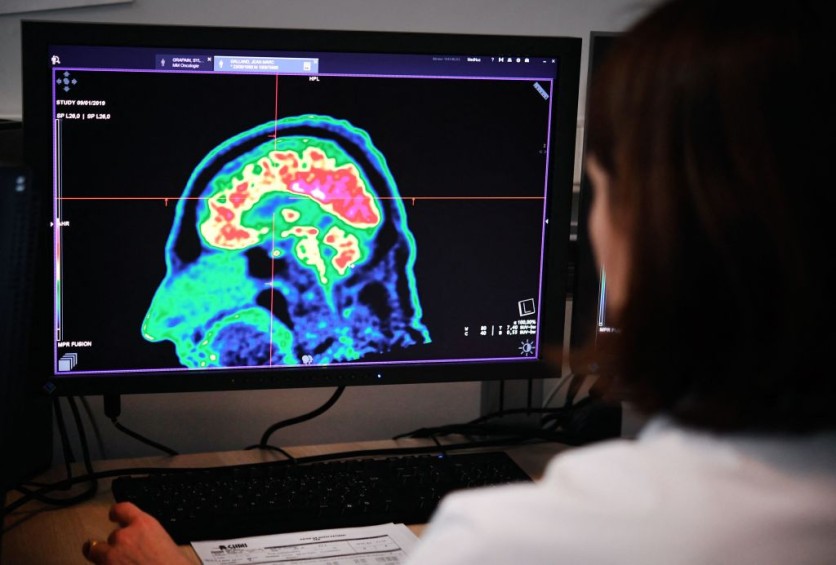

A picture of a human brain taken by a positron emission tomography scanner, also called PET scan, is seen on a screen on January 9, 2019, at the Regional and University Hospital Center of Brest (CRHU - Centre Hospitalier Régional et Universitaire de Brest), western France.

Reversing Alzheimer's

Following this discovery, Interesting Engineering reported that another research team initiated a study to investigate the potential for reversing amnesia associated with head trauma.

Dr. Mark Burns, the senior investigator of the study and a professor in Georgetown's Department of Neuroscience, as well as the director of the Laboratory for Brain Injury and Dementia, expressed hope regarding the research outcomes.

The findings suggest the possibility of developing treatments to restore the brain affected by head injuries to its normal state, potentially recovering cognitive function in individuals with impaired memory due to repeated head impacts.

Amnesia lacks a specific treatment, given its varied triggers. Healthcare practitioners address the situation by formulating a treatment plan that targets the underlying causes, making a significant impact.

Amnesia stemming from conditions that permanently disrupt brain function, such as cerebral hypoxia, brain tumors, Alzheimer's disease, or other neurodegenerative diseases, tends to be more enduring.

Conversely, memory loss induced by head trauma, stress, or illness-conditions that impact memory retrieval-may exhibit improvement over time. This suggests the potential for clinically reversing cognitive impairment caused by head impact.

Responding to Repetitive Head Impacts

Previous research efforts with a similar objective primarily focused on studying human brains afflicted with degenerative brain diseases linked to a history of repetitive head impacts.

However, Dr. Burns highlighted the distinctive goal of this study, aiming to comprehend how the brain responds to the low-level head impact often experienced by young football players.

The research utilized two groups of genetically modified mice to observe the memory neurons (engram) involved in the formation of new memories.

To create a new memory, both groups were subjected to a novel test, with the first group exposed to a high frequency of mild head impacts for a week, while the second group remained unexposed.

After a week, the control group demonstrated the ability to activate their memory engram upon encountering the room where they initially learned the memory. In contrast, the impacted mice struggled to recall the newly formed memory, indicating the cause of the induced amnesia.

To address this, EurekAlert reported that the lasers were employed to activate the memory engrams in the impacted mice, yielding positive results.

The research conducted by Georgetown University Medical Center in collaboration with Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, utilized a technique that may have limitations in its applicability to humans due to its invasive nature.

Nevertheless, the study demonstrated the possibility of reversing amnesia caused by head injuries through the activation of specific memory neurons.

Dr. Burns explained that ongoing research is exploring non-invasive approaches to signal to the brain that it is no longer at risk, with the goal of initiating a period of plasticity to restore the brain to its previous state.

ⓒ 2025 TECHTIMES.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.