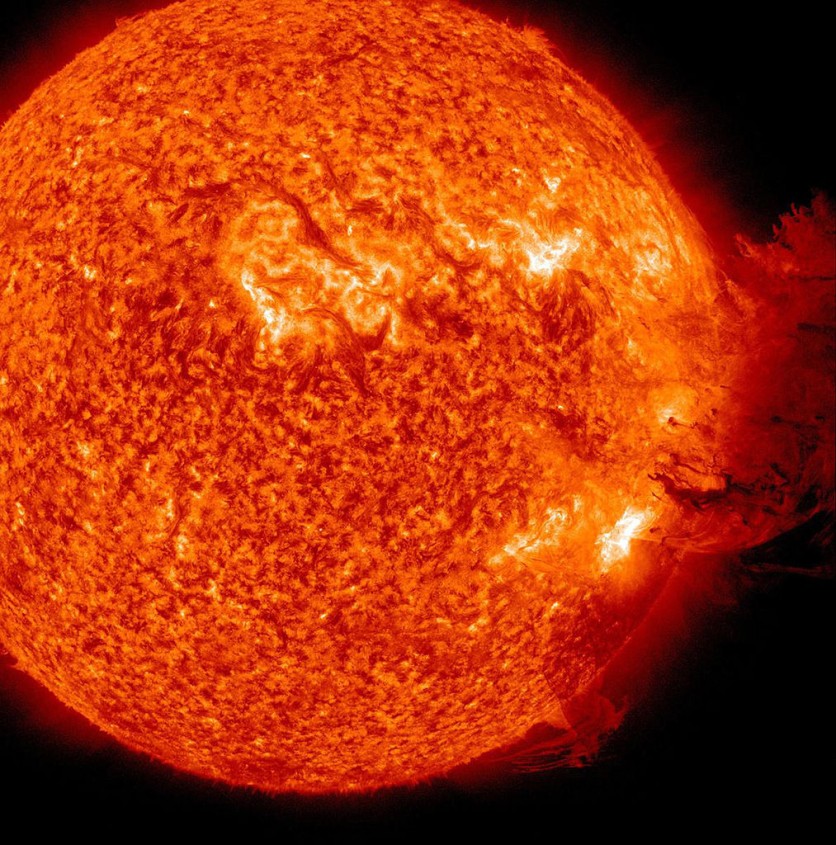

The sun ejected a medium-intensity solar flare that momentarily knocked out shortwave radio communication in the Pacific Ocean on Tuesday, Feb. 7.

The bright flare hailed from the sunspot AR3213 that is currently facing our planet, as reported first by Space.com.

Gigantic Sunspot

Several solar flares have been blasted off by the active sun in recent days, with one triggering a brief lapse in shortwave communications over the Pacific Ocean around 6:07 p.m. EST (2307 GMT), according to SpaceWeather.com.

The source region is AR3213, a massive Earth-facing sunspot that currently spans 62,000 miles (100,000 km) of the sun's surface.

AR3213 is a gigantic sunspot on the solar surface that is big enough to accommodate eight Earth-sized planets. It released an M-class solar flare on Feb. 7.

The event was caught in motion by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory.

Solar flares are electromagnetic radiation eruptions triggered by the unexpected release of energy held in powerful magnetic fields.

The intensity of these flares is graded based on their strength, with classes A, B, and C representing low-intensity flares and Class X representing high-intensity flares. Meanwhile, M-class flares have a moderate intensity.

The majority of energy emitted by solar flares is absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere. The intense radiation from medium to high-intensity solar flares, on the other hand, can disturb molecules in the higher layers of the atmosphere that are often used for radio communication and navigation.

Active Solar Cycle

The sun is becoming more active than ever in its 11-year cycle and is expected to peak by 2025. Hence, it will likely eject more solar flares and geomagnetic storms.

NOAA classifies geomagnetic storms on a scale ranging from G1, which can increase auroral activity and cause minor power outages, to G5, which is where large storms like the Carrington event occur.

The huge solar storm Carrington Event took place in September 1859, a few months before the Sun had its solar maximum in 1860.

According to a study, the annual average probability of a large solar storm is 4%, with a 0.7 percent risk of another Carrington storm.

The Earth was hit by a G3 storm in March 2021, which is a fairly common storm. However, even a G2 can cause significant damage. SpaceX demonstrated this in February 2022, when it lost 40 satellites due to a solar storm.

Related Article : 'Portrait of the Sun:' World's Most Powerful Solar Telescope Snaps The Face of the Sun in Crisp Detail

ⓒ 2025 TECHTIMES.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.