NASA will launch the eagerly anticipated Dragonfly mission to Titan, Saturn's biggest moon, in June 2027. By 2034, the nuclear-powered quadcopter weighing 450 kg (990 lbs) will land in the Selk crater region and explore Titan's surface and atmosphere to unravel the mysteries of this satellite.

As reported first by Universe Today, the expedition will specifically look at the organic environment, active methane cycle, and prebiotic chemistry of the moon. These objectives support Dragonfly's primary goal of discovering signs of potential life on Titan.

Is there Life on Titan?

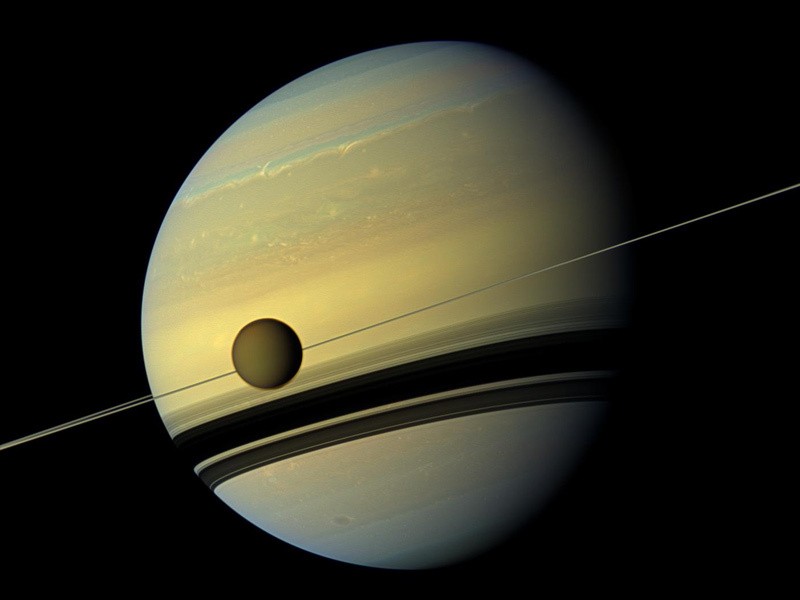

Scientists have raised the possibility of life on Titan for a very long time because it appears to have all the ingredients of a habitable area. This speculation has flared more immensely since the Cassini-Huygens mission, which spent 13 years between 2004-2017 investigating Saturn and its moons.

But now, a group of Cornell scientists compiled and examined radar photos collected by Cassini to ascertain the surface's characteristics. The landing site of the Dragonfly is depicted in great detail on the map, showing a landscape of sand dunes and broken-up frozen ground.

Léa Bonnefoy, a postdoctoral fellow at the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (IPGP)., the Carl Sagan Institute, and the Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science (CCAPS), spearheaded the study.

The research team, which focuses on locating and describing potentially habitable habitats throughout the Solar System, was led by associate professor of astronomy and Director of the Spacecraft Planetary Image Facility Alex Hayes. Bonnefoy was a member of this team.

"Dragonfly - the first flying machine for a world in the outer Solar System - is going to a scientifically remarkable area. Dragonfly will land in an equatorial, dry region of Titan - a frigid, thick-atmosphere, hydrocarbon world," Bonnefoy said in a Cornell Chronicle release.

Cassini's Radar Images

She added that the radar images from Cassini have a resolution of about 300 meters per pixel, roughly the size of a football field. The team has only seen less than 10% of the surface, and Bonnefey believes that there are many small rivers and landscapes that they are to discover.

The Cassini orbiter captured several radar photos of Titan and its numerous bigger moons over its orbits of Saturn. The Huygens lander, the orbiter's companion mission, was launched on Christmas Day 2004 and started its descent into Titan's dense atmosphere on Jan. 14.

The lander collected information on Titan's atmosphere during its two-hour descent to identify the aerosols and compounds that were present. River valleys that were not apparent in the orbiter's radar photographs might also be seen in the surface images it sent back, as per Universe Today.

Titan's atmosphere is mostly composed of nitrogen (about 95%), methane (about 5%), and other hydrocarbons and is nearly four times as dense as Earth's atmosphere.

With Titan's low gravity (13.8 percent that of Earth), this will allow Dragonfly to stay in the air and carry out tasks similar to those of a drone while studying Titan's atmosphere, surface, and methane lakes to find out more about the planet's makeup and if there are signs of life.

What Will We Get from Exploring Titan?

The information gathered by Dragonfly may help researchers better understand how life first appeared on Earth because Titan's current environment is thought to be similar to our planet's early history.

Another possibility is that life first appeared on Titan and is still present there now, most likely in the form of microbes.

According to Universe Today, these life forms' discovery and study may help us understand how and where life first appeared in the Solar System and how the building blocks may have been spread billions of years ago.

Related Article : 'Chrysalis,' Saturn's Lost Moon May be the Debris on Its Rings, Destroyed Millions of Years Ago

This article is owned by Tech Times

Written by Joaquin Victor Tacla

![Apple Watch Series 10 [GPS 42mm]](https://d.techtimes.com/en/full/453899/apple-watch-series-10-gps-42mm.jpg?w=184&h=103&f=9fb3c2ea2db928c663d1d2eadbcb3e52)