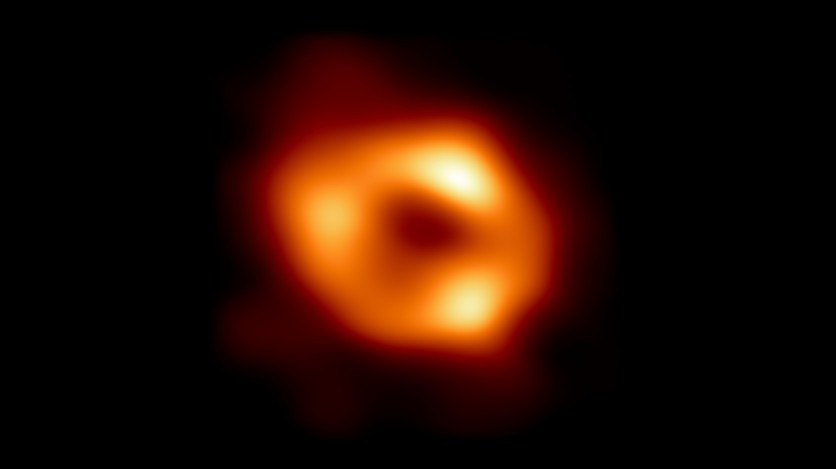

A group of over 100 scientists working among the Event Horizon Collaboration has snapped a cheeky photograph of the supermassive black hole residing at the Galactic Center of our galaxy. Though not necessarily one and the same, the black hole's general area (and hence it in turn) have been named Sagittarius A* (that's A star, to be clear).

While the picture itself may look nothing more than some blurry image of a distant star, it acts as a conduit for the future and a milestone in astrophysics, wherein radio telescopic technologies enhance the ways we look up at space. The group utilized the global consortium of said radio telescopes, called the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), which aided them not only in their most recent endeavor but likewise in the capturing of the very first image of a black hole back in 2019.

We finally have the first look at our Milky Way black hole, Sagittarius A*. It’s the dawn of a new era of black hole physics. Credit: EHT Collaboration. #OurBlackHole #SgrABlackHole

— Event Horizon 'Scope (@ehtelescope) May 12, 2022

Link: https://t.co/Ax7ECRVg8A pic.twitter.com/LRWizSYOy9

Today's find is remarkable in that it showcases not only the shadow of the black hole itself but also the high-energy field that encompasses it, which is more specifically where its namesake derives from. While most simply just refer to the supermassive black hole like Sagittarius A*, or Sgr A* for short, it more so refers to the block hole's general location and the astronomical radio source that surrounds it, which can get quite confusing.

Located only a mere 27,000 light-years away, the 4 million solar mass Sgr A* acts somewhat as a foundational pillar for our galaxy, the Milky Way. This central node within our galaxy was first discovered in 1918 by American astronomer Harlow Shapely, who utilized Cepheid variable stars to uncover a donut of star clusters floating in tandem around a region of space within the constellation Sagittarius. Sgr A* itself would not be found until much, much later in 2020, but the prevailing theory concluded that it was a supermassive compact object.

Related Article : 'Superblood' Moon is Coming this Weekend | Here's How to See it

Today, the Event Horizon Collaboratoion's discovery puts to rest doubts on what this distant object may be, proving its cosmic might as a supermassive black hole. Vastly diverging from their 1918 astronomer counterpart, the team of researchers utilized what's called Very Long Baseline Interferometry via the EHT. Essentially, each telescope scattered across the globe collates and measures the variations in the time it takes for light from a source in deep space to reach each group's telescope.

One of the group's leaders, José L. Gómez, the VLBI group, considers the find a total success gave the unimaginable difficulty required in taking such a shot. During a press briefing on Thursday, the VLBI group leader likens it to snapping a "clear picture of a running child at night," given the immense speeds of the supermassive black hole's surrounding gas. He adds, "You can imagine how crazy it drove us for many years."

Among the most interesting discoveries was the accretion rate of Sgr A*, which NASA Einstein Fellow at the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Sara Issaoun, denotes as incredibly undernourished. She says, "If you had the same diet as Sagittarius A* scaled to your mass, you'd eat one grain of rice every million years." The discovery thus proves that not all black holes are such hungry and destructive forces in the cosmos; some like a bit of abstinence, as well.

Following this major breakthrough, the team is thus building out far more advanced ways of cosmic photography through the construction of the Next Generation EHT, which will multiply the number of radio telescopes among the array to allow for, hopefully, far better imagery and potentially even dynamic films of black holes in the near future.

Read Also: NASA Snaps Intense Solar Flare from the Sun

ⓒ 2026 TECHTIMES.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.