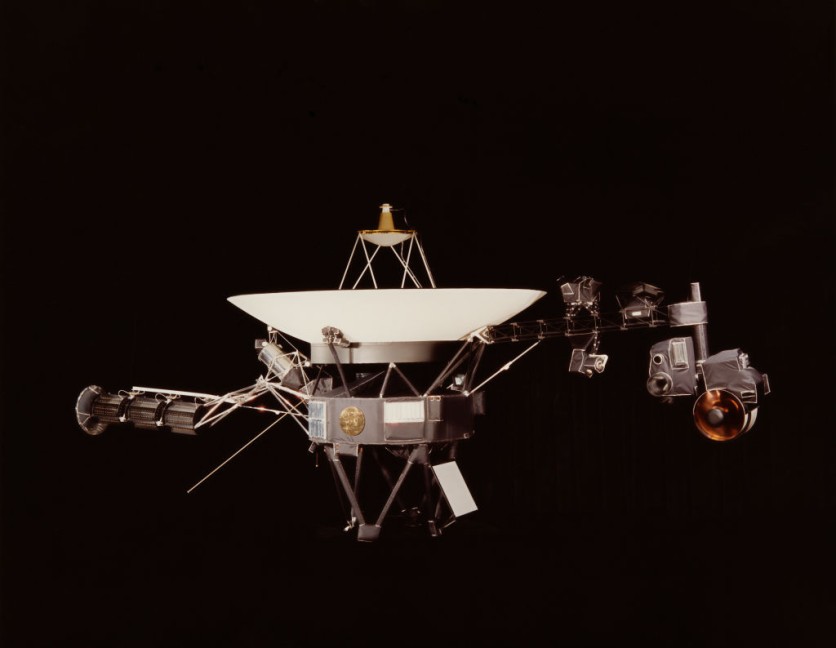

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) Voyager 2 mission is perhaps one of the most important and successful space missions the space agency has done, going around a grand tour of our solar system and having close encounters with planets aside from ours.

The Voyager 2's Grand Mission

On January 24, 1986, Voyager 2 was ready to meet and gather data from the icy planet Uranus, which proved to be incredibly successful.

According to NASA, the spacecraft flew within 50,600 miles (or 81,433 kilometers) from the seventh planet's icy cloud tops, capturing images of the planet, along with a massive swath of data that soon proved to be incredibly useful for scientists here on Earth.

Through the Voyager 2 mission, astronomers were able to have an in-depth look at the planet's atmosphere, the measurements of Uranus, revealing two new rings, a look at its 11 moons, and finally, the planet's magnetic environment.

With the mission, scientists were able to find out just how chilly the planet is, which drops below 353 degrees Fahrenheit.

Uranus' Plasmoid

However, scientists from back there had managed to overlook one detail about the data acquired by Voyager and the faraway planet itself, and experts were only able to find out about it 30 years after Voyager's Uranus flyby.

In a report by Inverse, it turns out that the spacecraft flew through a plasmoid.

A plasmoid is a massive structure of a planet's magnetic field that can strip it of its atmosphere, which means that the mysterious icy planet is being stripped of its atmosphere.

These giant plasma bubbles are sucked from the atmosphere and then hang off the end of the planet's magnetic field as it's being blown away by the solar wind, a phenomenon that is also known as magnetotail.

A Tiny, Squiggly Blip

But how did experts miss this detail?

According to the report, Voyager 2 only flew through the plasmoid for a mere 60 seconds of its 45-hour visit to Uranus, so it appeared as a tiny blip in the data brought by the spacecraft.

It was so small that scientists were unable to spot it for three decades.

The detail was only discovered this year by experts, who took a good look at the data acquired by Voyager 2 after 34 years and then spotting the small "squiggle," which is enough to raise a new set of questions regarding Uranus and its unique magnetic environment.

This is the first time plasmoids have been detected in Uranus and despite the new questions, the discovery could help astronomers further understand the processes that govern Uranus.

Since then, the icy planet has long been one of the most unique planets in our solar system.

For one, it's the only planet with a spin axis of 98 degrees, which means it's also the only planet that spins on its side, resulting in unique magnetic field points that are 60 degrees away from its spin axis.

That means when the planet spins, the space carved by its magnetic field, also known as the magnetosphere, wobbles slightly, according to NASA.

Related Article : Israeli Beresheet Spacecraft Allegedly Brought Microscopic Organisms to the Moon, Possibly Taking Over

This article is owned by Tech Times

Written by: Nhx Tingson

ⓒ 2025 TECHTIMES.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.