Neuroscientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) published a study in Cell on October 27 identified the cause of the declining motivation to learn among elderly.

MIT Institute Professor Ann Graybiel said that it is harder to keep a "get-up-and-go attitude" as people age. "This get-up-and-go, or engagement, is important for our social well-being and for learning - it's tough to learn if you aren't attending and engaged," added Graybiel who is also a member of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research and the study's senior author, according to a SciTech Daily report.

The paper's lead authors are MIT research scientist Emily Hueske and University of Texas Assistant Professor Alexander Friedman who is a former research scientist in MIT.

After studying mice, MIT neuroscientists discovered a brain circuit critical for keeping such motivation. Such research on mice states that aging has effects on brain circuit that is critical for learning to make vital decisions, which are linked to cost and reward evaluations.

Read also: Mobile Game Improves Children's Mental Health This Pandemic As Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Motivation to learn and Aging

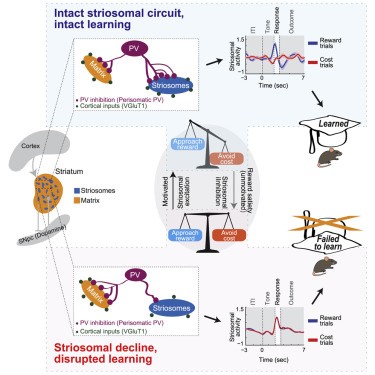

The striatum is included in a collection of brain centers called basal ganglia, which is linked to emotion, habit formation, addiction, and controlling voluntary movement. Graybiel lab has been researching for several decades about clusters of cells called striosomes, which are spread across the striatum. She has also discovered striosomes years ago, but their function remained unknown since they are located deep within the brain, which make them difficult to image using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

According to a news report published in MIT website, older mice between 13 and 21 months, which is equivalent to human aged 60 year old and above, had declined learning engagement compared to younger mice. A similar loss of motivation was found in the mouse model for the Huntington's disease, which is a neurodegenerative disorder affecting the striatum and striosomes.

Also, numerous mental health disorders have affected the subjects' ability to evaluate costs and rewards of an action. These range from anxiety, depression as well as PTSD conditions. This means that a person undergoing depression may undervalue a rewarding experience while those who suffer from drug addiction may overvalue drugs while underestimating other matters such as their family or job.

Hueske noted that a person as represented by a mouse "may value a reward so highly" while overwhelming the risk of having possible cost. In contrast, another subject may wish to evade the cost by rejecting all rewards. "These may result in reward-driven learning in some and cost-driven learning in others," Hueske added.

Genetically-targeted drugs to boost activity

When the researchers used genetically targeted drugs to boost activity in the striosomes, they found that the mice became more engaged in task performance. Conversely, suppressing striosomal activity led to disengagement.

MIT researchers are now working on potential drug treatments to encourage this circuit. They also suggest training patients to improve activity through biofeedback, which could offer another possible way to enhance cost-benefit evaluations.

Friedman said "patients may be able to activate their circuits correctly" if scientists could identify a mechanism, which triggers the reward and cost subjective evaluation while using a modern technique to deploy it through biofeedback or psychiatrically.

Related article: Move Over Neuralink, This 'Stentrode' Brain Chip Lets Paralyzed Patients Control Computers with Their Minds!

This is owned by Tech Times

Written by CJ Robles

ⓒ 2025 TECHTIMES.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.