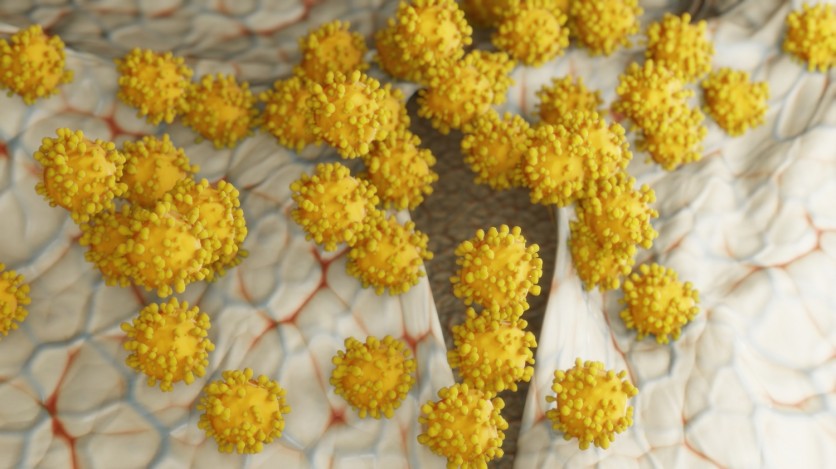

The world is currently suffering from a coronavirus known as the SARS-CoV-2, which brings the highly infectious disease, COVID-19, and a close relative of the SARS and MERS viruses. It is believed that the virus came from either bats or pangolins and jumped to humans.

Now, researchers have discovered six new coronaviruses in different species of bats.

The Discovery of Six New Coronaviruses

According to a report by the New York Post, researchers have found the new coronaviruses in three species of bats in Myanmar, namely the Greater Asiatic yellow house bat, the Horsefield's leaf-nosed bat, and the wrinkle-lipped free-tailed bat.

Researchers working with the Smithsonian's Global Health Program collected more than 750 samples of fecal matter and saliva from 464 bats from 11 different species.

They acquired the samples from three locations in the country where humans are usually in close contact with these bats and the wildlife in general due to cultural and recreational activities.

After getting the samples, the researchers analyzed their genetic sequences and compared them with the genome of known coronaviruses.

From that, they were able to find new viruses that were discovered for the first time, plus one that has been found in Southeast Asia, but never in Myanmar.

The six new coronaviruses were then given names: PREDICT-CoV-9, which is found in the Greater Asiatic yellow house bat, the PREDICT-CoV-82 and the PREDICT-CoV-47, which were from the wrinkle-lipped free-tailed bat, and the PREDICT-CoV-92, PREDICT-CoV-93, and the PREDICT-CoV-96, which were found from the Horsefield's leaf-nosed bat.

Nevertheless, LiveScience noted that these new coronaviruses are not genetically related to the SARS-CoV-2 or the novel coronavirus that brought COVID-19.

Read also: Coronavirus Update: NHS Creates 'Score' System, Causing Elderly Patients Denial of Critical Care

Why the Research is Essential

The study has been recently published in the journal PLOS ONE and took place from 2016 to 2018.

The scientists discovered these new coronaviruses while they were surveying bats from Myanmar as part of the PREDICT program, which is government-funded research that aims to identify any infectious diseases that may potentially hop from animals to humans.

"Viral pandemics remind us how closely human health is connected to the health of wildlife and the environment," said Marc Valitutto, the lead author of the study and a former wildlife vet with the Smithsonian's Global Health Program.

"Worldwide, humans are interacting with wildlife with increasing frequency, so the more we understand about these viruses in animals-what allows them to mutate and how they spread to other species--the better we can reduce their pandemic potential," he added.

Could the New Coronaviruses Pose a Threat?

It is believed that there are still thousands of coronaviruses present in bats and other mammals that are yet to be discovered.

According to the director of the Smithsonian's Global Health Program and co-author of the study, Suzan Murray, most coronaviruses do not pose any threat to humans.

However, the PREDICT program is essential since they can identify these diseases early on with the animals, and they could conduct investigations to know which of these diseases could potentially cause threats to public health.

The team consists of different scientists from different sectors, including the Smithsonian, the University of California, Davis, Myanmar's Ministry of Health and Sports, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, and Myanmar's Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation.

ⓒ 2025 TECHTIMES.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.